Wordy Wednesday: Ralph Meets Lily

I am violating the first rule of Wordless Wednesday, which is to let the photos speak for themselves. I feel compelled to give you the backstory.

We acquired Ralph from the pound seven years ago, and it immediately became apparent that he is very neurotic. Most of all, he is anti-social. I am the only person he willingly interacts with. He no longer growls at Greg, but he just tolerates him. He still barks at and runs away from our own children–after seven years! And when our grandchildren come over, Ralph hides and won’t come out.

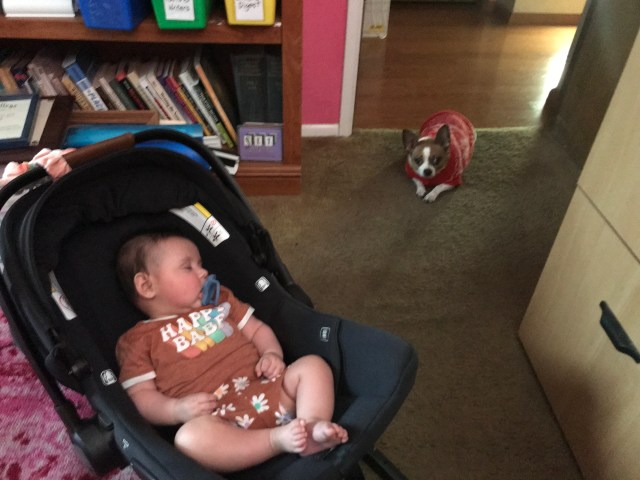

When our granddaughter Lily was about six months old, her parents dropped her off at our house so we could have some quality time with her while Katie and Michael grabbed a bite to eat. Ralph went to his favorite hideaway. Greg and I had lots of cuddle time with her, and ultimately, when she got fussy, I put her in her car seat so she could doze while I worked on the computer.

Well, Ralph finally came out to investigate. I guess a sleeping baby isn’t all that threatening.

That was two years ago. He still hides whenever anyone comes over.

Review of Hearing God through Biblical Meditation by Mark Vinkler

Don’t you long to hear God’s voice? I know I have heard it on occasion. But I can’t summon it at will. I eagerly read this book in 2021, but didn’t review it then. I had to reread half of it to refresh my memory. Again, I started it eagerly.

Hearing God Through Biblical Meditation begins with wonderful suggestions. Stillness. Seeing Jesus with the eyes of one’s heart. Knowing that Jesus is always with you. “God’s voice in your heart often sounds like a flow of spontaneous thoughts.”

Virkler identifies four keys to successful meditation: Quiet down, tune to spontaneity, look for vision, and journal.

Each chapter ends with exercises, which I confess I thought about briefly, but didn’t do.

And then I got bogged down.

With virtually every chapter, Virkler gives us new points to internalize. Five ways to tell whether you’re hearing God’s voice. Four pillars of meditation. Seven steps to receive revelation knowledge through meditation. (When asking for revelation, “you are asking the Holy Spirit to unveil that which is under the surface. . .you are asking Him to shine light on what that passage means and how it can be applied.”) Twelve points to properly handling scripture. Fourteen basic principles for interpreting scripture. Four disciplines of inductive Bible study. Seven (actually way more than seven) questions about what is going on in the passage of Scripture. I can’t keep that many points in mind at one time. His process becomes cumbersome for me.

I wish Virkler would go back and rewrite this book, simplifying it, concentrating on the four keys, discussing them in detail, and including some of the rest of the material in the context of illuminating the keys. In other words, not telling us everything there is to know on the subject of Biblical meditation, but just giving us practical suggestions to facilitate hearing God’s voice.

Since Virkler doesn’t rewrite his work according to my whims, my suggestion for someone who wants to read this book is—take the journaling idea very seriously. Buy a notebook. Read this book slowly, like maybe a chapter a week. Do the exercises. Do your daily Bible reading and apply the points in the current chapter. See which points are helpful to you in your meditation, and make note of them in your notebook. When you’re all through reading this book, come up with your own points to deepening your meditation process. You can make this book work for you.

Video of the Day: Musical Instrument Repair Shop

Please, if you love children, if you love music, watch this video. It’s longer than the videos I usually post, 40 minutes. But it is imperative that we make sure all children have access to musical instruments. There should be a shop like this in every school district in our country, in the world. Let’s talk to our legislators about it.

Wisdom From Past Presidents

“There are men and women who make the world better just by being the kind of people they are. They have the gift of kindness or courage or loyalty or integrity. It really matters very little whether they are behind the wheel of a truck or running a business or bringing up a family. They teach the truth by living it.” — James Garfield

“It is amazing what you can accomplish if you do not care who gets the credit.” — Harry S. Truman

“Life takes its own turns, makes its own demands, writes its own story, and along the way, we start to realize we are not the author.” — George W. Bush

“In matters of style, swim with the current; in matters of principle, stand like a rock.” — Thomas Jefferson.

“Do what you can, with what you have, where you are.” — Theodore Roosevelt

“If you’re walking down the right path and you’re willing to keep walking, eventually you’ll make progress.” — Barak Obama

“Our nation is shaped by the constant battle between our better angels and our darkest impulses. It is time for our better angels to prevail.” — Joe Biden

“No person was ever honored for what he received. Honor has been the reward for what he gave.” — Calvin Coolidge

“If we want to invest in the prosperity of our nation, we must invest in the education of our children so that their talents may be fully employed.” — Bill Clinton

“The strongest of all governments is that which is most free.” — William Henry Harrison

“Peace is more than just an absence of war. True peace is justice, true peace is freedom, and true peace dictates the recognition of human rights.” — Ronald Reagan

“We have come tardily to the tremendous task of cleaning up our environment. We should have moved with similar zeal at least a decade ago. But no purpose is served by post-mortems. With visionary zeal but the greatest realism, we must now address ourselves to the vast problems that confront us.” — Gerald Ford

“History teaches, perhaps, very few clear lessons. But surely one such lesson learned by the world at great cost is that aggression, unopposed, becomes a contagious disease.” — Jimmy Carter