Three Book Reviews: Little Fires Everywhere, Sea of Tranquility, Where the Crawdads Sing

Here are three popular novels that lived up to their hype, in that they compelled me to neglect my husband and my responsibilities. I wanted to read them more than I wanted to do chores or sleep.

Little Fires Everywhere by Celeste Ng starts with the climax of the story, then gives us the back story little by little until we truly understand how the character was compelled to do what she did. The book centers around teenager Pearl Warren and her single mother, Mia, a photographer/artist. They’ve lived a nomadic, hand-to-mouth lifestyle, but thought maybe now they could put down roots.

But it’s also the story of the well-to-do Richardson family, with professional parents and four children. They become the Warrens’ landlords, and Mrs. Richardson insists on helping Mia by hiring her as a part-time cook and cleaning lady for the family. Son Moody becomes Pearl’s first friend, and when Pearl meets his sister, Lexie, they also become best friends.

The descriptions of Mia’s creative process held me enthralled. Also, the relationship that grows between Mia and the Richardsons’ youngest daughter, the troubled Izzy, fascinated me. Mia is the first person to really see Izzy, have compassion for her, and suggest some life strategies for her (though they may not have been the most positive strategies).

This is a story that appeals to me as an adult, but could also be enjoyable for mature young adult readers. My reservation for young readers is that there is a lot of sexual activity among the characters, especially for Lexie, a senior in high school, and Pearl, who’s only a freshman.

It’s a story about secrets, about love, about friendship, about betrayal.

Sea of Tranquility by Emily St. John Mandel. If you’ve read other books by Mandel, you probably know that some of her characters make appearances in more than one book. Sea of Tranquility is no exception; some characters from The Glass Hotel figure in this quirky time travel novel.

The events in this book happen in 1912, 1918, 1990, 2008, 2020, 2203, and 2401, though not chronologically. Pandemics happen, and also moon colonies. But mostly this book details the investigation by the Time Institute of a mysterious anomaly in the space/time continuum and agents who break the rules while traveling back in time.

I don’t read a lot of science fiction. I am flabbergasted that someone could come up with a story line like this. I was mystified all the way though, but in the end, it mostly made some kind of sense. Sea of Tranquility is the fourth of Mandel’s books that I’ve read. She has become one of my favorite writers, and I must read all of her books.

Where the Crawdads Sing by Delia Owens. I did not see the 2022 movie, but all the chatter about it made me buy the novel.

Kya Clark’s family lived isolated in the North Carolina coastal marshes. She was the youngest of five children. When she was six, her Ma fled from her abusive husband. One by one, her much older siblings also left the home, until Kya was left alone with her neglectful alcoholic father, who frequently disappeared for days at a time.

She goes to school for one day, but it doesn’t go well. She realizes she can’t go to school, because then she’ll be put into a foster home. She learns to evade the Child Services people. She’s really not welcome in town, where people consider her a dirty marsh rat, not fit for polite company.

For a period of time, Pa doesn’t drink, and life goes well for them. Kya cleans the house and teaches herself how to cook from her memories of Ma in the kitchen. Pa takes Kya fishing with him. She daydreams that her Ma will come back and the three of them will have an idyllic life together in the marsh. A letter comes from Ma; Pa reads it, burns it, and leaves. When he comes back days later, his sobriety is over, and Ma never does come home.

And when Kya’s ten, Pa doesn’t return from one of his absences.

Kya discovers she can gather mussels and smoke fish she’s caught and sell them to Jumpin’, the man who runs a little store on the wharf. Then she can use the money to buy everything she needs from his store. Jumpin’ and his wife Mabel help Kya to get by, teaching her how to plant and care for a garden, making sure she has clothes suitable for her needs.

A boy she met out on the water becomes a good friend to her, offering her gifts of interesting feathers, teaching her how to read. She teaches herself to draw and paint the birds and insects, flora and fauna of the marsh. Tate introduces her to poetry, and eventually she becomes proficient at writing, and some of her poems are accepted for publication, as well as books.

A young man, well-respected in the town, falls from the fire tower to his death. The investigators suspect foul play, and the young woman who grew up wild in the marsh, Kya, becomes their prime suspect. She’s eventually arrested, but she’s acquitted at trial. She ultimately becomes Tate’s common law wife and they live out their days alone in the marsh.

Author Delia Owens is a wildlife biologist who spent a lifetime doing research in Africa. She is the co-author with Mark Owens of three volumes of nonfiction: Secrets of the Savanna, The Eye of the Elephant, and Cry of the Kalahari. In Where the Crawdads Sing, her vivid descriptions make the marsh one of the characters of the story. Her use of words is nothing short of beautiful. As for the mystery, I was guessing (wrong) through to the very end of the book.

All three of these books transported me into their worlds. Isn’t that exactly what we want a book of fiction to do for us? I heartily recommend them all.

The Blessing

We sang this beautiful song in church yesterday, and it touched me deeply. I hope it blesses you too.

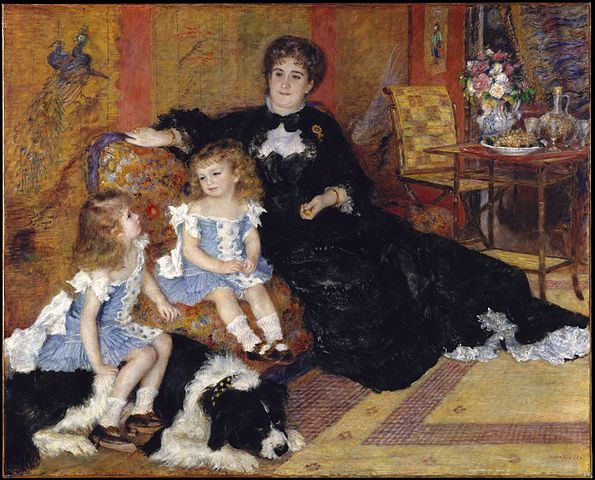

Renoir

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919) was one of the leading painters of the French Impressionist movement.

He grew up in Paris, in close proximity to the Louvre. Although the young Renoir had a natural talent for drawing, he exhibited a greater skill for singing. His musical talent was nurtured by his teacher, the composer Charles Gounod. However, due to the family’s financial difficulties, Renoir discontinued his music lessons and left school at the age of thirteen to become an apprentice at a porcelain factory.

Although Renoir excelled at porcelain work, he grew bored with it and frequently escaped to the galleries of the Louvre. The owner of the factory recognized his apprentice’s talent and admitted it to Renoir’s family. Soon, Renoir started taking art lessons to prepare for entry into the famous Ecole des Beaux Arts.

In 1862, he began studying art under Charles Gleyre in Paris. There he met other young painters including Claude Monet. At times during the 1860s, he did not have enough money to buy paint. Although Renoir first started exhibiting paintings at the Paris Salon in 1864, recognition was slow in coming.

In the late 1860s, through the practice of painting light and water en plein air (outdoors), he and his friend Claude Monet discovered that the color of shadows is not brown or black, but the reflected color of the objects surrounding them, an effect known today as diffuse reflection.

Renoir was inspired by the style and subject matter of previous modern painters Camille Pissarro and Édouard Manet. After a series of rejections by the Salon juries, he joined forces with Monet, Sisley, Pissarro, and several other artists to mount the first Impressionist exhibition in April 1874, in which Renoir displayed six paintings. Although the critical response to the exhibition was largely unfavorable, Renoir’s work was comparatively well received.

Hoping to earn a livelihood by attracting portrait commissions, Renoir displayed mostly portraits at the second Impressionist exhibition in 1876. He contributed a more diverse range of paintings the next year when the group presented its third exhibition. Renoir did not exhibit in the fourth or fifth Impressionist exhibitions, and instead resumed submitting his works to the Salon. By the end of the 1870s, particularly after the success of his painting Mme Charpentier and her Children (1878) at the Salon of 1879, Renoir was a successful and fashionable painter.

In 1881, he traveled to Madrid to see the work of Diego Velázquez. Following that, he traveled to Italy to see Titian’s masterpieces in Florence and the paintings of Raphael in Rome. It was that trip to Italy when he saw the works by Raphael, Leonardo da Vinci, Titian, and other Renaissance masters, that convinced him that Impressionism was the wrong path for him.

On January 15,1882, Renoir met the composer Richard Wagner at his home in Palermo, Sicily. Renoir painted Wagner’s portrait in just thirty-five minutes. That same year, he contracted pneumonia which permanently damaged his respiratory system.

In 1883, Renoir spent the summer in Guernsey, one of the islands in the English Channel with a varied landscape of beaches, cliffs, and bays, where he created fifteen paintings in little over a month. By the mid-1880s, however, Renoir had broken with the Impressionists. For the next several years he painted in a more realistic style in an attempt to return to classicism.

While living and working in Montmartre, Renoir employed Suzanne Valadon as a model, who posed for him (The Large Bathers, 1884–1887) and many of his fellow painters; during that time she studied their techniques and eventually became one of the leading painters of the day.

In 1890, Renoir married Aline Victorine Charigot, a dressmaker twenty years younger than he who, along with a number of the artist’s friends, had already served as a model for Luncheon of the Boating Party (she is the woman on the left playing with the dog), and with whom he had already had a child, Pierre, in 1885. After marrying, Renoir painted many scenes of his wife and daily family life including their children and their nurse. The Renoirs had three sons: Pierre (1885–1952), who became a stage and film actor; Jean (1894–1979), who became a filmmaker of note; and Claude (1901–1969), who became a ceramic artist.

Around 1892, Renoir developed rheumatoid arthritis. In 1907, he moved to the warmer climate of “Les Collettes”, a farm at the village of Cagnes-sur-Mer, Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur, close to the Mediterranean coast.

Renoir painted during the last twenty years of his life even after his arthritis severely limited his mobility. He developed progressive deformities in his hands and ankylosis of his right shoulder, requiring him to change his painting technique. Renoir remained able to grasp a brush, although he required an assistant to place it in his hand.

Renoir’s paintings are notable for their vibrant light and saturated color, most often focusing on people in intimate and candid compositions. The female nude was one of his primary subjects.

His initial paintings show the influence of the colorism of Eugène Delacroix. He also admired the realism of Édouard Manet, and his early work resembles his in the use of black as a color. Renoir admired Edgar Degas’ sense of movement.

A prolific artist, he created several thousand paintings. The warm sensuality of Renoir’s style made his paintings some of the most well-known and frequently reproduced works in the history of art. The single largest collection of his works—181 paintings in all—is at the Barnes Foundation, in Philadelphia.

Click on the pictures below to enlarge and show titles.

Material for this article came from Wikipedia.