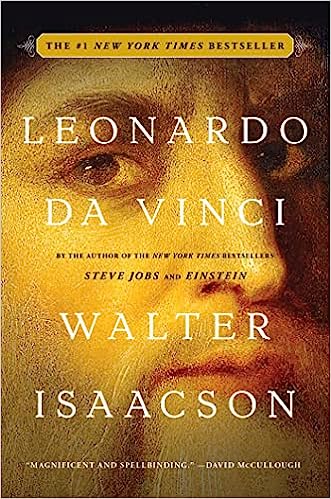

It took me more than four years to finish this book. Not that it’s boring—it’s the opposite of boring! Walter Isaacson built relationships with some of the foremost authorities on da Vinci and researched this book meticulously. He produced a biography of great depth, beauty, and empathy, and gives us a detailed study of the genius that is Leonardo. At 525 pages of text (and another 45 pages of notes), this book is an ambitious read (although you could enjoy just looking at the 142 gorgeous illustrations, including more than 100 color reproductions of Leonardo’s paintings and notebook pages). For every hour that I spent reading the book, I needed a few days to just digest and ponder.

I’ll tell you a few of the things I learned about Leonardo from reading this book—but only a small serving of the cornucopia the book provides. You’re going to want to read this for yourself.

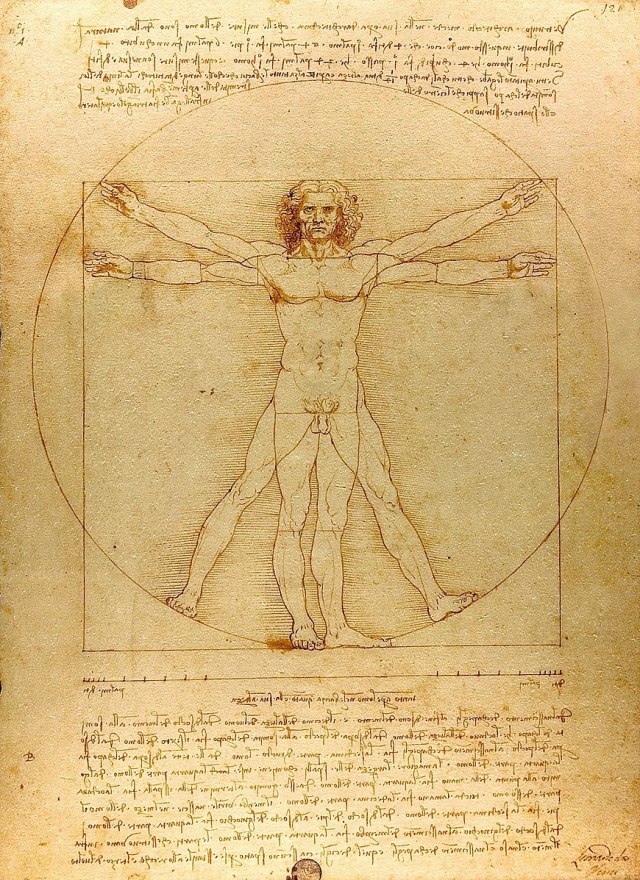

You’ve heard of Leonardo’s workbooks. 7200 pages still exist, each one crowded with notes, scribbles, and drawings because he couldn’t afford to waste paper. (No Target back-to-school sales in those days.) He wrote left handed, and also backward, so that unless you were very perceptive, you’d need a mirror to read what he wrote. (I can’t make out his script at all. Plus, it’s in Italian.) In the notebook he wrote observations, designs, his deepest thoughts, and notations of things he wanted to do, such as “describe the tongue of a woodpecker.” He was interested in all areas of science, from biology to engineering to architecture. He liked to put on pageants and shows with lots of elaborate costumes, sets, and special effects.

And he was a master painter, especially of employing the technique known as chiaroscuro, the contrasting of light and shadow for achieving the illusion of three-dimensions on a two-dimensional canvas. He pioneered sfumato (Italian for “smoke”), the blurred outline and mellowed colors that allow forms to dissipate. Isaacson does a remarkable job of describing and evaluating Leonardo’s paintings, even though he is a general historian, not an art historian. His research, knowledge, and writing skill make this book a joy to read.

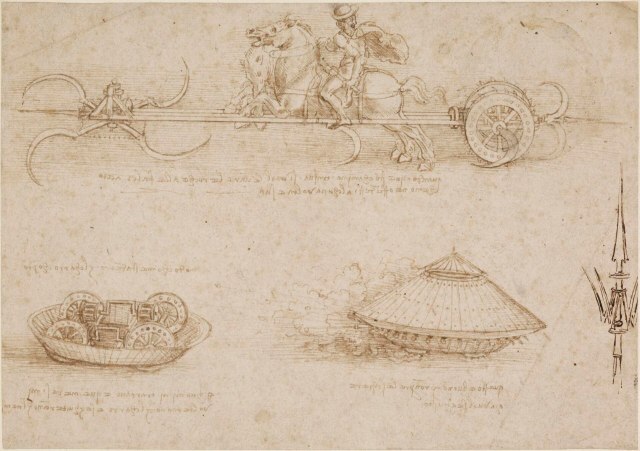

Some of the contraptions Leonardo drew, like the aerial screw, thought by many to be an early design for a helicopter, were probably props for a theater production, the making of which occupied the artists’ workshops of Florence when Leonardo was an apprentice there. The Medicis ruled Florence, and they often put on spectacles, like productions that necessitated Christ being raised into heaven by a crowd of angels. How would you like that assignment in 1470?

When Leonardo moved from Florence to Milan in 1482, the study of anatomy there was pursued primarily by medical scholars, as opposed to Florence where the anatomists were artists. He began dissection in Florence and continued in Milan. He saw art and science as intertwined—knowledge of anatomy was useful for his art; the science of it excited his sense of beauty.

Leonardo was a prolific inventor. He devised an accurate odometer that counted the turns of a vehicle’s wheels and translated them into units of measure. But many of his inventions were never constructed, just drawn in detailed diagrams in his notebooks.

He was also a skilled musician. He was an accomplished lyre player, and also a singer. He improvised many songs, but never wrote any down (how uncharacteristic for someone who wrote so much). He also invented instruments. He invented a special lyre that had five strings played with a bow and two plucked with the fingers. He invented combination-instruments designed to look like birds or dragons or skulls.

If Leonardo had a fatal flaw, it was his failure to complete his projects, even his commissions. This was due partly to his perfectionism, and partly to being detoured by the next shiny thing. Isaacson says “he preferred the conception to the execution;” he was “more easily distracted by the future than he was focused on the present. He was a genius undisciplined by diligence.” (That must be why I have so many unfinished novels on my computer—I’m just like Leonardo.)

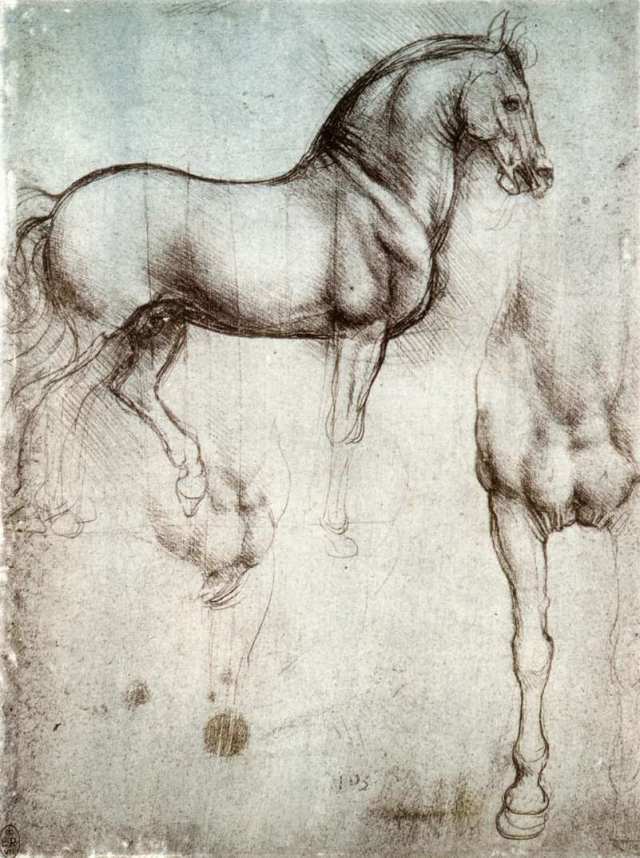

In 1489, Leonardo earned a much-desired commission: to design a monument to Francesco Sforza, a 23-foot high equestrian statue, much larger than any comparable monument that existed at that time. As he got involved in the project, he ignored the rider (Sforza) and focused on the horse, referring to the statue as il cavallo (the horse). In preparation, he made detailed anatomy studies of the different parts of the horse (aided by dissections) in his notebooks, also recording his thoughts and plans, detailed instructions of how the bronze would be poured into the mold. The mold needed to be placed in a pit, which raised many technical problems (for example, digging too deep would hit the water table).

Sadly, the horse project was never completed. In 1494 the French attacked the Italian states, and the bronze for the statue was repurposed to make cannons. When the French invaded Milan, their archers used the clay model of the horse for target practice, destroying it. Only his notes remain to show how much time, energy, and love he devoted to the project. (More modern artisans eventually made a statue from Leonardo’s plans.)

Leonardo studied the canals in Milan, wondering about how he could apply what he learned to Florence. Florence had lost control of Pisa and wanted it back, because it had access to the sea. The voyages of Columbus and Vespucci made seaports very desirable for supplies and launching expeditions. Leonardo came up with a scheme of diverting the River Arno from its course, cutting off Pisa’s access to the sea and giving it to Florence. He did a time-and-motion study and determined it would take approximately 1.3 million man-hours, or 540 men working 100 days, to dig an appropriate ditch. He also designed a machine to move earth, with 24 buckets.

The excavation was not overseen by Leonardo, but by a hydraulic engineer who ignored Leonardo’s specifications. Instead of digging one ditch to a depth of 32 feet, he dug two ditches only 14 feet deep, much shallower than the Arno. it didn’t work; the waters did not enter the ditches, and a violent storm caused the ditch walls to collapse. The project was abandoned.

After the invention of the printing press, Italy’s first publishing house opened in 1469. Leonardo became a collector and voracious reader of books, and by 1504 owned over 100 volumes, including 40 science books, almost 50 books of poetry and literature, 10 on art and architecture, 8 on religion, and 3 on mathematics.

Leonardo employed the scientific method, observing, measuring, experimenting, formulating hypotheses, testing them, and modifying them. 200 years before Newton articulated his first law, Leonardo wrote in his notebook: “A body in motion desires to maintain its course in the line from which it started . . . every body in motion continues to move so long as the influence of the force that set it in motion is maintained in it.”

Chapter 18 is a fascinating study of Leonardo’s The Last Supper, including an explanation of the “complex perspective” he used to minimize distortion when the painting was viewed from the sides of the room.

In 1500 Leonardo, then 48, was back in Florence. Michelangelo, age 25, was also there. A rivalry ensued when they were given assignments to paint battle scenes on opposite walls of the Council Hall in Florence. Michelangelo treated Leonardo with disdain. Leonardo protested that the statue of David ought to have a covering over his genitalia. (A leafy garland was made for it, which David wore for at least 40 years.)

Neither Michelangelo nor Leonardo finished his war mural for the Council Hall. Leonardo had technical problems with perspective and distortion and adherence; Michelangelo abandoned his to work on the Sistine Chapel.

Leonardo worked as a military engineer for Cesare Borgia (the son of Pope Alexander VI), as he conquered town after town from Florence to the Adriatic coast. Leonardo designed all sorts of machines that had military applications, and made many maps. He only lasted eight months at this work, then quit because of Borgia’s brutality.

In 1503 Leonardo received a commission from Francesco del Giocondo to paint a portrait of his wife, Mona Lisa. It was never delivered. Leonardo carried it with him from Florence to Milan to Rome and to France, constantly making small refinements to it. It was still in his possession at his death.

From 1508—1513 Leonardo dissected cadavers and made detailed anatomical studies, better than any in previously available texts. In the process, he wrote the first description of arteriosclerosis.

Leonardo figured out how heart valves work by making a glass model of a heart and watching how water traveled through it. In the 1960s a team of researchers at Oxford, using dyes and radiography to observe blood flow, confirmed that Leonardo was correct.

So much of Leonardo’s research was never published during his lifetime, simply because he didn’t pursue publication. His study was motivated by curiosity. He recorded his findings, but for himself. The fact that he didn’t publish diminished his impact on the history of science.

Isaacson tells Leonardo’s story more or less chronologically, but he also explores each area of Leonardo’s interest: entertainment, proportion, birds and flight, mechanical arts, mathematics, painting and portraiture, engineering, sculpture, hydraulics. As I read, I took 12 pages of notes in preparation for writing this review. I have shared only a few highlights of my notes. This book is so rich—one of the best biographies I’ve ever read. I will reread it for sure. I also plan to read each of Isaacson’s other biographies. I once heard him interviewed about his 2021 book The Code Breaker, about Jennifer Doudna and gene editing, and he is as articulate and engaging in person as he is in his writing.

Thank you for writing about Leonardo. That biography is amazing, and I am glad to know about it. Your summary is stunning.

LikeLiked by 1 person